|

Glim n. (obsolete, rare; Scots; slang)

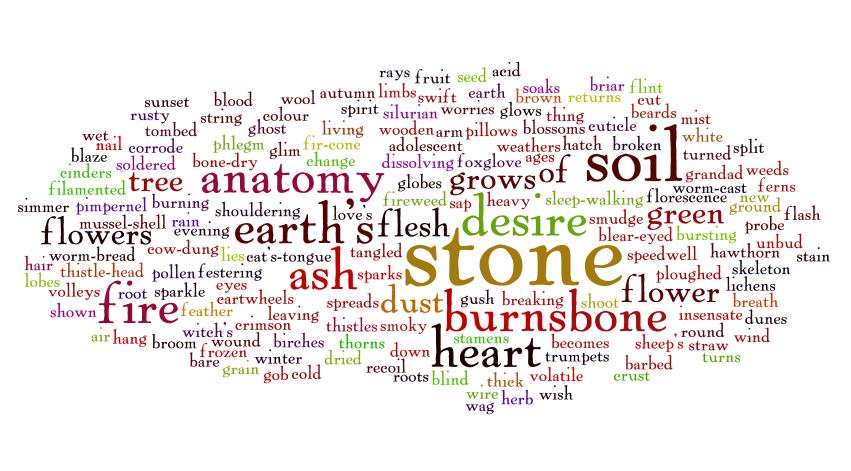

As we enter the middle days of February the darkest days and longest nights of the year have passed, and thoughts turn to the coming spring, or to love and desire, perhaps, if we’re following the prompts of St. Valentine’s Day. Although Nicholson is not an obviously passionate or romantically inclined poet, there are a number of his poems which do deal with themes of love and desire, somewhat objectively and impersonally at times, and as a facet of his deeper philosophy. Desire in this context can be equated with the forces of life, with energy itself, with the power which Dylan Thomas called ‘The force that through the green fuse drives the flower...’. Nicholson – born in the same year as Thomas – is not so far as might be imagined from sharing some commonality of outlook with the more famous poet. And both poets were highly alert to the sonic energies of words, and to the spark and crackle that can flame across a poem when an absolutely precise word-choice, of whatever register or origin, sets off a chain-reaction that lights the reading or listening mind. In Nicholson’s second collection of poems, Rock Face (1948), there is a slightly puzzling and relatively long poem called ‘The Anatomy of Desire’ in which the word ‘glim’ appears. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) gives three main senses for this word: 1: ‘brightness’ (obsolete or rare) 2: ‘a passing look, a glimpse’ (Scots and obsolete), and ‘a light of any kind’ (slang). Nicholson doesn’t use the word ‘glim’ in any of the other poems in his Collected Poems, although he does employ the related words ‘glimmer’ (four times) and ‘gleam’ (in both the noun and verb forms). ‘Glim’ is a word in its own right, and not merely a shortened form of ‘glimmer’, as the OED etymology suggests. The OED is unsure about the origins of ‘glim’ in Old English or Old Norse, although it acknowledges that ‘some of the continental Germanic languages have a word of coincident form and meaning’, including the Swedish dialect glim (‘flash’), modern German glimm (‘spark’) and Flemish glim, glimp (‘glow’, ‘glance’, ‘passing appearance’). It is the online Dictionary of the Scots Language, however, which clearly links the word to Norwegian and to Swedish: ‘Cf. Norw. dial. glim, a glimmer, lustre, glima, to glimmer, glitter, Sw. dial. glim, a gleam…’, whilst Joseph Wright’s magisterial English Dialect Dictionary (1898) tells us that as a noun the word was in general dialect and slang use both in Scotland and England. In Nicholson’s poem ‘The Anatomy of Desire’ ‘glim’ is one of the few words which edges into dialect use (‘gob’, meaning ‘a mass’ or ‘a lump’ being another), and it sits amongst several words relating to light and fire: flame, smouldering, blaze, sparks, cinders, burning, flash, ash, smoky, sparkle – and so forth. These are words of energy, and they give energy to a poem that could otherwise seem rather abstract. The anatomy of desire Is not like fire – Insensate spirit Swift as a wish. Flowers of flame Unbud in a glim Of crimson, a simmer Of smouldering down... At this period of his life, Nicholson was deeply interested in the poetry of the Metaphysicals and in 17th-century writings in general (see e.g. Nicholson’s ‘Memories of the W.E.A.’, a typescript held at the John Rylands Library, Manchester). In this case, both the title of the poem and its argument – a poetic discussion of the true and paradoxical nature of desire – probably derive from his engagement with the period. To understand the poem one needs to know that the word ‘anatomy’ can mean several things, including a detailed analysis to determine the nature of what is under discussion, and a skeleton. The title itself is modelled on Robert Burton’s ‘The Anatomy of Melancholy’ (1621) and, possibly also on John Donne’s ‘The First Anniversary: An Anatomy of the World’ (1621). The imagery of the poem seems to be quite neatly divided between the positive and the negative, the living (‘blood’, ‘sap’, ‘flower’, ‘pollen’, ‘tree’, ‘flesh’) and the dead (‘flint’, ‘cinders’, ‘ash’, ‘worm-bread’, ‘cold’, ‘stone’) – yet as the poem progresses it becomes clear that life and death, organic and inorganic matter, are inextricably intertwined and form part of a cycle in which the most death-like element of the natural world – stone – is perceived as the essence of life itself, ‘the anatomy’, or skeleton, on which desire (i.e. the life-force) is built. The little ‘glim / Of crimson’ which marks the start of ‘Flowers of flame’ ‘unbudding’ is the clue to help us realize that what seems dead, black coal laid down in the earth millennia since, was once alive, displaying in the play of its flames a likeness to the flowers, stems, stamens, and pollen it used to be. That light, warmth and energy still give life, not only to the humans who benefit from it in the present, but also to the soil to which the ashes and cinders return, ultimately allowing new flowers to grow, new seeds to fall. But why does Nicholson choose to use the word ‘glim’ to initiate this process of meditation rather than, for example, ‘gleam’ or ‘glimmer’? I think the answer lies not only in its etymological links to the old Norse language, which left its marks on the Cumbrian dialect, but also in the precision it gives to the image. A ‘glim’ is both a spark and a small (sometimes darkened) light. It is the little seed from which Nicholson’s anatomizing will grow, and the torch which shines its light into the heart of the paradox the poem explores. Moreover the word ‘glim’ carries out its work not only as an important nucleus within the image-structure of the poem, but also as a sound-element which grows and expands into a chain of related sounds: glim, crimson, simmer, flint, cinder, gush, green, glows, grows, grain... Each sound-kernel in its turn initiates its own network of inter-related sounds, so that the whole soundscape of the poem may be imagined as being formed from the crystal of ‘glim’. The ‘anatomy of desire / Is only a stone’, Nicholson says at the end of this poem, but that stone skeleton underpins and sustains life, and the little word ‘glim’ has helped to shine its own light on the essence of that ‘only’. The fact that it is also a dialect word which has travelled through time, linking us to our ancient Germanic and Norse relatives, as well as to our nearer Scottish and Northern English neighbours, is something I really value. It has the magic of sound in it still: sound that means something like what it says – ‘glim’, ‘gleam’, ‘glow’, ‘glisten’, ‘glitter’... brightness and smallness together, caught sight of in the corner of your eye, or scattered across space and time to reach your ear, your seeing. Antoinette Fawcett February 2015 After-notes If you are interested in the concept of sound symbolism you could check out this brief discussion about ‘gl-’ words in English here. The academic Piotr Sadowski has written an article called ‘The Sound as an Echo to the Sense: Iconicity of English gl-Words’ which can be read in the book The Motivated Sign (eds Olga Fischer and Max Nänny). And here is an interesting discussion about the poetry of a shampoo brand-name, which also focuses on the ‘gl-’ sound. To get an idea of the richness of Nicholson’s vocabulary in this poem, and the place of ‘glim’ within it, take a look at this word-cloud made from the words of the poem. The word cloud was made using Wordle, a toy for generating “word clouds” from text. Another version of the same information, with word-counts included, can be seen here. This one was made with TagCrowd – less pretty, but useful for its more precise statistics.

|

The poem itself can be read in Nicholson’s Collected Poems pp. 159-161. The collection Rock Face, in which the poem was first published in book form, is still available on-line, and can be found in some libraries.